Seoul - This is a proposal submitted to Hon. Moon Jae-in, the President of the Republic of Korea on 23 May 2018 by Gobinath 'SiGo' Sivarajah -

1.1 Overview of PyeongChang 2018

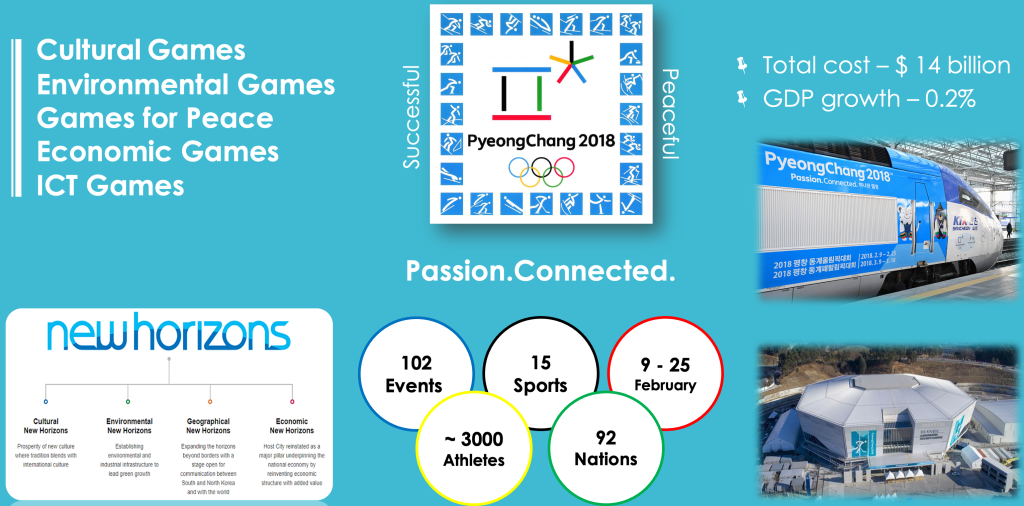

PyeongChang 2018, the 23rd Winter Olympic Games proved a successful and peaceful Winter Olympic Games, promoting regional development and prospects for Korean unification. The PyeongChang Olympic Games ran from 9 – 25, February 2018. Approximately 3000 athletes from 92 National Olympic Committees (NOCs) participated in 102 events – all Games records. Moreover, 25 Olympic records and three world records were broken during the PyeongChang Winter Games.

In the lead-up to the Games, North Korea had launched 11 missiles over the Pacific Ocean which threatened not only South Korea but also the globe in taking part in the Olympic Games. Some countries were expressing concern over attending the 2018 Games. Suddenly, one month prior to the Games, everything came on the right track. North and South Korea marched together in the opening ceremony and players from both nations played in a joint women’s ice hockey team which added a positive impact to the Olympic Movement – Peace Olympics, later, PyeongChang was called the safest Olympics ever in history.

The Games totally cost USD 14 billion. Of that, USD 12 billion was spent on infrastructure, including a high-speed rail line (KTX), venues, expressways, and roads. Moreover, Mr LEE Hee-beom, the president of the PyeongChang 2018 Organising Committees (POCOG) mentioned in a speech delivered to the Dream Together Master (DTM) students at Seoul National University that POCOG, which was in the red last year, now anticipates a surplus, with Olympic ticket sales – among other revenue items – at 100.9 per cent and the Games boosted South Korean GDP by 0.2 per cent.

Since Korean population density is dramatically increasing, the KTX, expressways and roads will be highly used and will generate more revenue for the country which is ideal and good for the country. On the other side, the main arena, which was used for the opening and closing ceremonies, is going to be demolished. Sadly, there is no proper legacy plan found to be to sustain the newly built venue facilities for long-term usage. In this case, the sports facilities’ legacy has been a question mark even after finishing the games, for the last two months. Also, it costs a lot even to keep the facilities just like the Olympic museum. Therefore, there is a necessity to develop a sustainability and legacy plan for the Pyeongchang 2018 facilities to utilize the venues without any loss in the future.

2.1 Previous Olympic Games Legacy Failures – Abandoned Olympic Venues

Throughout the Olympic history, host cities spend billions of dollars on sports facilities infrastructure constructions and renovations for every Olympics to show itself globally as a modern, well-designed and well-run metropolis with modern facilities and infrastructure symbolic of the quality of life and economic investment. But, once the Games are over, it is obviously seen that most of the Olympic facilities become white elephants. There are many stadiums and venues in the past Olympics are abandoned, looted and damaged as they are not used due to huge maintenance costs and a lack of support and coordination between commercial providers and public governing bodies (Vassilios Ziakas, 2014).

Kissoudi (2008) mentioned that the Athens 2004 Olympic Games provided the host city with an excellent opportunity, but later, it became a splitting headache for the government, which experienced harsh criticism from all the political parties. Now, the sporting extravaganza, many of its once-gleaming Olympic venues now lie abandoned.

Azzali (2016) concluded about the Sochi 2014 economic side was probably the most unsuccessful one as the final expenditure of USD 55 billion, was the most expensive Olympics ever. The event was mainly publicly funded, and all the facilities were built over capacity, with the railway and road infrastructure itself costing more than USD 10 billion. All the sports venues are now closed or underutilized, and the park, with the exception of the weeks before the Formula 1 race, is abandoned.

Nine venues were built for Sarajevo 1984 Winter Olympic Games. After their sixteen-day spotlight, the venues were immediately abandoned as the region grew unstable and ultimately fell into civil war less than ten years later. Several, such as the bobsled venue, were used as military installations throughout the Bosnian war. They have remained abandoned ever since (Ponic, 2017).

Many venues of the previous host cities, such as Rio 2016, Beijing 2008, Grenoble 1968, and Berlin 1936 have been abandoned. This obviously explains that many countries hosted Olympic Games without any long-term legacy plans which lead them to the disaster. Also, past experiences showed that outcomes from staging major events are mostly harmful and negative, especially if one considers how sports facilities and their surroundings are utilized after the end of the event. In the end, these abandoned venues teach a lesson that the Olympic Games are a giant waste of money.

2.2 Success of PyeongChang 2018, Prior to the Games

The success of an Olympic Games or mega sporting event is not only about the game quality or infrastructure developments but it is depending on its legacy place as well. One of the missions of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) – ‘promoting a positive legacy from the Olympic Games to the host cities and host countries’ is important to spread the Olympic spirit, which can be achieved through pre and post-Olympic Games activities.

In this way, Dream Program was initially launched by PyeongChang in 2004 as a part of its bid for the 2010 Olympic Winter Games to expand winter sports, promote friendship among youths, and contributed to peace around the world. Dream Programme has been held 14 times from 2004 to 2017 and played a huge role in introducing winter sports to the youths in Korea. The IOC, winter international federations such as the International Ski Federation and International Skating Union, the foreign media and National Olympic Committees were the primary stakeholders of the programme. Since then, 1,574 youths including 105 with disabilities from 75 countries participated. Many athletes benefited from the tropical developing countries especially, from Africa and Asia, 521 and 534, respectively.

Dream Program offered an educational program and seven million people benefited through the program during which they learned about Olympic values.

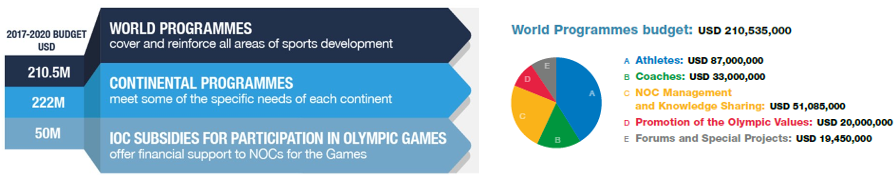

3.1 Olympic Solidarity Plan 2017-2020

Olympic Solidarity is an IOC organisation and its aim is to organise assistance for all the National Olympic Committees (NOCs), particularly those with the greatest needs, through multi-faceted programmes prioritizing athlete development, training of coaches and sports administrators, and promoting the Olympic ideals.

In PyeongChang 2018, more than 270 athletes and 13 teams benefited from the Olympic Solidarity scholarship. This scholarship included a fixed monthly training grant to cover training and coaching costs, and a travel subsidy which enabled the holders to participate in Olympic qualification competitions.

The Olympic Solidarity plan 2017-2020 is developed and its development and assistance budget is over USD 500 million with a strong focus placed on athletes’ training and development in line with the Olympic Agenda 2020 to develop youngsters, athletes, leaders and coaches. 21 world programs are offered in this plan under major five units of athletes, coaches, NOC management and knowledge sharing, promotion of the Olympic values, and forums and special projects.

The key objectives of the Olympic Solidarity plan 2017-2020 are,

- increasing assistance for athletes and supporting NOCs in their efforts to protect clean athletes,

- focusing on the NOCs with their greatest need, and

- promoting Olympic Agenda 2020 concepts through advocacy and education.

3.2 Warm-weather and Developing Countries in Winter Sports

Nowadays, developing countries are much interested in developing sports in their regions. Six countries stepped into Winter Olympics for the very first time at PyeongChang 2018. Interestingly, four countries out of the above six, Malaysia, Ecuador, Eritrea, and Nigeria are warm-weather developing countries. Approximately 40 tropical nations have already participated at least in a Winter Olympics, ten each from Africa, and, Central and South America, eight from the Caribbean, and six Asian countries, in which, most of them are developing countries.

The Dream program helped many warm-weather and developing countries to initiate winter sports. Sri Lanka, Vietnam, Pakistan, Hong Kong, Ecuador, Rwanda and the UAE are some of the countries that benefited from the program. Since they do not have snow and ice rink facilities in their countries they could not able to continue their practices to enhance their skills and become elite athletes to compete at regional or international level competitions.

By considering the newly built available facilities at the PyeongChang, financial aid from the Olympic Solidarity and local bodies, and identified major issues and needs for developing countries in developing winter sports around the globe, I have proposed a feasible sustainability and legacy plan for PyeongChang 2018 Winter Olympic facilities in the next part of this proposal.

4.1 Sustainability and Legacy Plan

PyeongChang 2018 is already considered a successful Olympic Games. It should not go unused after the games and become a white elephant. PyeongChang facilities are newly built, as it was the very first Winter Olympic Games for South Korea, with frugal costs compared to the previous two Winter Olympics. By considering previous host cities’ issues, I have proposed a model to sustain the facilities as the PyeongChang 2018 Legacy in order to create a win-win situation for the local and international sport institutions.

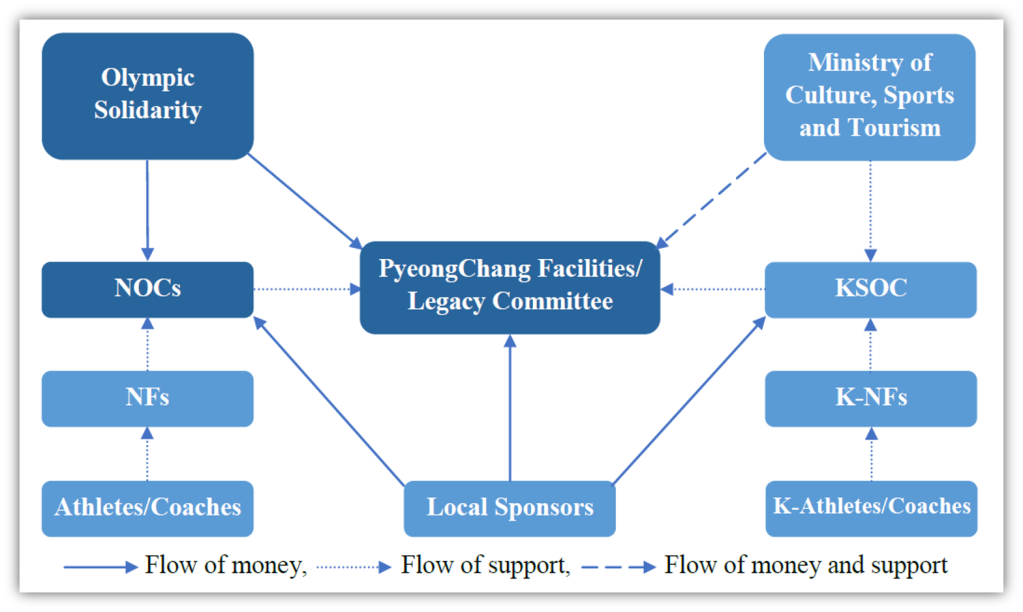

In order to create a sustainability and legacy plan, PyeongChang facilities, the NOCs of developing countries and Olympic Solidarity are identified as key stakeholders to sustain the PyeongChang 2018 facilities. Also, there are other organisations and sponsoring companies will also be working in a partnership manner. Figure.2 sustainability and legacy model explains it in detail.

Figure 2 illustrates that some of the organisations provide or receive only money, some receive support and some other organisations provide both money and support. This is how a symmetrical model was developed to sustain the PyeongChang 2018 facilities.

The following chapter explains the roles and responsibilities of each organisation in detail for the success of this sustainable and legacy plan for PyeongChang 2018.

4.2 Winter Sports Facilities

4.2.1 Facilities in Developing Countries

The biggest problem of most of the developing countries and newly winter sports introduced countries is building new winter sports venues. Even if they build an ice rink, again there will be a question, of how to maintain it at a high cost. Winter sports facilities are often harder to maintain and building sporting facilities for high cost because of requiring higher technologies and resources for maintaining ice and snow. Also usually a smaller number of people practice winter sports compared to summer sports.

On the other hand, if it is a warm-weather or tropical country, it is almost impossible to set up a snow sporting arena even with artificial snow. To all those requirements for maintenance, high-tech facilities with the best humidity management technologies must be stable, controlled air conditions inside the facility, regardless of season or weather outside and have better snow and ice conditions.

4.2.2 PyeongChang Facilities

PyeongChang 2018 Winter Games competition facility consists of two main clusters, the PyeongChang mountain cluster and the Gangneung coastal cluster which consist of seven and five venues, respectively. Also, PyeongChang facilities were newly built to launch New Horizons in winter sports and create a sustainable legacy for Gangwon Province and the Republic of Korea. Now, the most successful Winter Olympic Games hosting country, South Korea has a great opportunity to provide similar to those European training facilities and the service to the world of winter sport, especially in Asia and Africa. As a part of the Pyeongchang 2018 Winter Olympic Legacy, South Korea has already succeeded with Dream Program which invited many youths, from little snow regions or from countries where winter sports are not widely known, to Pyeongchang.

To implement this proposal, firstly, a steering committee should be formed under the name of sustainability and legacy committee for PyeongChang facilities (SLCPF) which could be formed with members from the Korean Sport and Olympic Committee (KSOC), Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism (MCST), experts and Korean leading sports sponsors or partners. Their primary task for PyeongChang facilities will be to provide training facilities such as sporting venues, equipment, coaches, and accommodation.

4.3 Participant Countries and Athletes

PyeongChang 2018 was launched with the slogan of ‘Passion.Connected.’ which refers to ‘a world open to any generation anywhere, anytime, to open new horizons in the continued growth of winter sports’. In this proposal, this slogan leads to the legacy plan. The NOCs who do not have any winter sports facilities in their countries, especially in warm-weather countries will get benefits through this plan. Athletes can be beginners or elite athletes, but all the athletes’ participation must be through their respective NOCs.

Professional winter sports athletes should take their training in authentic snow and ice arenas. Artificial snow is not suitable if they are going to take part in international-level competitions. That is why most winter sports elite athletes go to European countries, such as Norway, Switzerland, Sweden, and other countries for professional training camps to train and prepare themselves for international-level events. An athlete pays approximately USD 650 for a seven-day training camp in Switzerland. Most athletes train more than a week, and it takes years as well. Therefore, PyeongChang facilities will be more attractive to the Asian and African developing countries as the facilities are newly built with modern technologies.

4.4 Funding and Supports

4.4.1 Olympic Solidarity

Olympic Solidarity is the prime funding organisation for this project. This project could be fixed under world programmes. As shown in the Figure.1, USD 87 million and USD 33 million have been already allocated for athletes and coaches, respectively for 2017-2020. For the long-term success of this project, the NOCs and SLCPF have to approach the Olympic Solidarity to request funds according to their number of athletes and their needs. This will cover the athletes’ necessary needs for the training at PyeongChang as well as the coaches’ costs and facilities’ sustainability costs.

Above-mentioned both parties can approach Olympic Solidarity funding under the three sections mentioned in the Olympic Solidarity Plan 2017-2020 manual.

- Athletes

- Team support grant

- Continental athlete support grant

- Youth Olympic Games – athlete support

2. Coaches

- Technical courses for coaches

- Development of a national sport system

3. Promotion of the Olympic values

- Sustainability in sport

- Olympic education, culture and legacy

4.4.2 Local Sponsors and supports

The Olympic Solidarity funding definitely will not be enough to cover all the costs. Therefore, the NOCs will have to seek for local sponsors to fulfil the total cost for the success of this project.

Also, the MSCT will support the SLCPF directly, and athletes and coaches will be supported by their respective NOCs via their NFs for the success of this project and in the development of winter sports in their country and the globe.

4.5 Programs and Competitions

Since this project is going to be funded and supported by many local and international sport entities and provides service to all, therefore, the PyeongChang facilities could be named as PyeongChang Olympic Training Centre so as to provide winter sports for all. Under this PyeongChang Olympic Training Centre, I propose some feasible programs and competitions.

- Grass-root level and youth athletes’ training programs

- Elite athletes’ training programs

- Coaches coaching programs

- PyeongChang 2018 Mini Olympics: In order to commemorate PyeongChang 2018, national or regional level competitions for the youths every year in February.

4.6 Benefits of the Project

Through this project, many parties will be benefited in many ways. But, it will highly impact South Korea’s many developments, mainly,

- Pyeongchang facilities will sustain for long-term;

- PyeongChang will become a centre for all the warm-weather developing countries;

- Current expenditure on PyeongChang facilities will reduce;

- Winter sports will develop;

- Gangwon province’s regional development will improve;

- Job opportunities will be created;

- It will strengthen strategic partnerships with NOCs, Olympic Solidarity and local sponsors; and

- Tourism will eventually increase.

The proposed strategic approach to sustain the PyeongChang 2018 facilities is also aligned with the objectives of the legacy strategic approach of the IOC. This proposal is developed with the available resources, based on the previous Olympic facilities’ abandoned experiences to meet the Olympic legacy’s four objectives, and make a win-win situation for all relevant bodies. Also, the proposal is made by considering the economic stabilities and utilising the facilities with maximum usage rate. Lastly, as the IOC President Thomas Bach mentioned in his farewell address that PyeongChang 2018 is a “Games of New Horizons”, this proposal will also carry the name as the legacy of PyeongChang 2018.

Reference

- Azzali, S. (2016). The legacies of Sochi 2014 Winter Olympics: an evaluation of the Adler Olympic Park. Urban Research & Practice, 10(3), 329-349. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17535069.2016.1216586

- IOC Legacy Strategic Approach: Moving Forward. (2017, 12 5). Lausanne: International Olympic Committee.

- Kissoudi, P. (2008). The Athens Olympics: Optimistic Legacies – Post-Olympic Assets and the Struggle for their Realization. The International Journal of the History of Sport, 1972-1990. doi:10.1080/09523360802439049

- OLYMPIC AGENDA 2020. (2014). Lausanne: International Olympic Committee.

- Olympic Charter. (2017). Lausanne: International Olympic Committee.

- Olympic Solidarity Plan 2017-2020. (2017). Lausanne: International Olympic Committee, Olympic Solidarity.

- Ponic, J. (2017, September 8). Abandoned Olympic Venues. How They Play, p. https://howtheyplay.com/olympics/AbandonedOlympicVenues. Retrieved from https://howtheyplay.com/olympics/AbandonedOlympicVenues

- The Legacy of PyeongChang 2018. (2018, 03 30). Retrieved from http://www.pyeongchang2018.com: https://www.pyeongchang2018.com/en/news/the-legacy-of-pyeongchang-2018

- Vassilios Ziakas, N. B. (2014). Post-Event Leverage and Olympic Legacy: A Strategic Framework for the Development of Sport and Cultural Tourism in Post-Olympic Athens. Journal of Sports, 87-101.

Abbreviations

ANOC – Association of National Olympic Committees

DTM – Dream Together Master

GDP – Gross Domestic Product

IOC – International Olympic Committee

KNFs – Korean National Sports Federations

KSOC – Korean Sport and Olympic Committee

KTX – Korea Train eXpress

MCST – Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism

NFs – National Sports Federations

NOCs – National Olympic Committees

POCOG – PyeongChang Organizing Committee for the 2018 Olympic Games

SLCPF – Sustainability and Legacy Committee for Pyeongchang Facilities

UAE – United Arab Emirates

USD – United States Dollar